Plagiarism and Design

In an article in the excellent graphic design forum designobserver.com, graphic designer Michael Beirut says he was shocked when he realized he had imitated a Willi Kunz design from 1975:

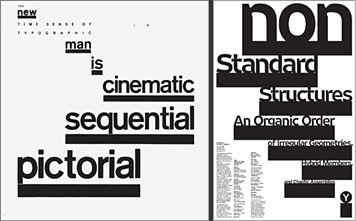

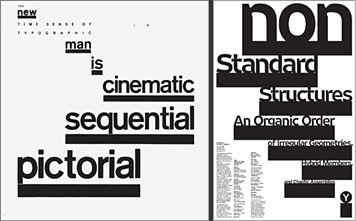

Here are both designs:

[Beirut includes a link to a copyright website where you can hear both George Harrison's and the Chiffons' songs and judge if he infringed.]

We all reference, we all imitate. Sometimes I'm surprised at how easy it is to recall someone else's words or style. Other times, I'll write something and then think I deleted it, so I'll rewrite it and then find the original (that's actually happened more than once) -- I'm always shocked at my inability to remember my own words accurately.

Imitation in art, sincere or unconscious is one thing -- and that's what Michael Beirut was doing -- but copying -- which is what Kaavya Viswanathan was doing -- is another. If Ms. Viswanathan's plots and themes were similar to a published writer's, that would be imitation. She copied, and then changed a few proper nouns.

Michael Beirut had an article in Design Observer about a year ago which dealt with a similar situation. In Designing Under the Influence he describes meeting a designer nine months out of school who had something in her portfolio that looked familiar. He wrote:

Beirut figures one of a number of things happened:

Turns out this debate comes up often in design. Beirut writes: "We've debated imitation, influence, plagiarism, homage and coincidence before, and every time, the question eventually comes up: is it possible for someone to "own" a graphic style? Legally, the answer is (mostly) no. And as we sit squarely in a culture intoxicated by sampling and appropriation, can we expect no less from graphic design?"

And then he links to a Design Observer article by his colleague William Drenttel called Bird in Hand: When Does A Copy Become Plagiarism?, which looks at two designs, photos, that feature hands with small birds perched on them. One of the photos is from a well-known photographer. The other, later photo, is a stock photo that a design magazine used for its cover. Drenttel writes:

But one of the photographers had made his career on pictures of birds in hands, and had published a critically acclaimed (in the design community) book on it. Why would a design magazine use a stock photograph from another photographer that looks so obviously similar? Bad judgement if nothing else.

So why, Drenttel asks, is written plagiarism considered more serious than design plagiarism? Good question.

Drenttel links to a 2004 New Yorker article by Malcolm Gladwell called Something Borrowed. It's worth revisiting in today's climate of Kaavya Viswanathan.

Gladwell begins by telling about a play that borrowed way too liberally from a real person's life, and then from a profile Gladwell wrote on the person. But further on in the article, he visits a friend who "works in the music industry" who plays him endless songs that resemble other songs in scandalous ways:

This friend could apparently go on like that all night. And that's what music is about for him -- endless riffs on previous riffs. Gladwell writes:

Couldn't that go for all art?

"Did I think of it consciously when I designed my poster? No, my excuse was the same as Kaavya Viswanathan's: I saw something, stored it in my memory, forgot where it came from, and pulled it out later — much later — when I needed it. Unlike some plagiarists, I didn't make changes to cover my tracks. (At various points, Viswanathan appears to have changed names like "Cinnabon" to "Mrs. Fields" and "Human Evolution" to "Psych," as one professor at Harvard observed, "in the hope of making the result less easily googleable.") My sin is more like that of George Harrison, who was successfully sued for cribbing his song "My Sweet Lord" from an earlier hit by the Chiffons, "He's So Fine." Just like me, Harrison claimed — more credibly than Viswanathan — that any similarities between his work and another's were unintended and unconscious. Nonetheless, the judge's ruling against him was unequivocal: "His subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious did not remember... That is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished."

Here are both designs:

[Beirut includes a link to a copyright website where you can hear both George Harrison's and the Chiffons' songs and judge if he infringed.]

We all reference, we all imitate. Sometimes I'm surprised at how easy it is to recall someone else's words or style. Other times, I'll write something and then think I deleted it, so I'll rewrite it and then find the original (that's actually happened more than once) -- I'm always shocked at my inability to remember my own words accurately.

Imitation in art, sincere or unconscious is one thing -- and that's what Michael Beirut was doing -- but copying -- which is what Kaavya Viswanathan was doing -- is another. If Ms. Viswanathan's plots and themes were similar to a published writer's, that would be imitation. She copied, and then changed a few proper nouns.

Michael Beirut had an article in Design Observer about a year ago which dealt with a similar situation. In Designing Under the Influence he describes meeting a designer nine months out of school who had something in her portfolio that looked familiar. He wrote:

The best piece in her portfolio was a packaging program for an imaginary cd release: packaging, advertising, posters. All of it was Futura Bold Italic, knocked out in white in bright red bands, set on top of black and white halftones. Naturally, it looked great. Naturally, I asked, “So, why were you going for a Barbara Kruger kind of thing here?”

And she said: “Who’s Barbara Kruger?”

Okay, let’s begin. My first response: “Um, Barbara Kruger is an artist who is…um, pretty well known for doing work that…well, looks exactly like this.”

[This is an untitled Barbara Kruger design from 1987.]

“Really? I’ve never heard of her.”

Beirut figures one of a number of things happened:

One: My twenty-three year old interviewee had never actually seen any of Barbara Kruger’s work and had simply, by coincidence, decided to use the same typeface, color palette and combinational strategy as the renowned artist.

Two: One of her instructors, seeing the direction her work was taking, steered her, unknowingly or knowingly, in the direction of Kruger’s work.

Three: She was just plain lying.

And, finally, four: Kruger’s work, after have been so well established for so many years, has simply become part of the atmosphere, inhaled by legions of artists, typographers, and design students everywhere, and exhaled, occasionally, as a piece of work that looks something like something Barbara Kruger would do.

Turns out this debate comes up often in design. Beirut writes: "We've debated imitation, influence, plagiarism, homage and coincidence before, and every time, the question eventually comes up: is it possible for someone to "own" a graphic style? Legally, the answer is (mostly) no. And as we sit squarely in a culture intoxicated by sampling and appropriation, can we expect no less from graphic design?"

And then he links to a Design Observer article by his colleague William Drenttel called Bird in Hand: When Does A Copy Become Plagiarism?, which looks at two designs, photos, that feature hands with small birds perched on them. One of the photos is from a well-known photographer. The other, later photo, is a stock photo that a design magazine used for its cover. Drenttel writes:

"We all know that ideas come from many sources: they recur, regenerate, take new forms, and mutate into alternative forms. In the world of design and photography, there seems to be an implicit understanding that any original work can and will evolve into the work of others, eventually working its way into our broader visual culture."

But one of the photographers had made his career on pictures of birds in hands, and had published a critically acclaimed (in the design community) book on it. Why would a design magazine use a stock photograph from another photographer that looks so obviously similar? Bad judgement if nothing else.

So why, Drenttel asks, is written plagiarism considered more serious than design plagiarism? Good question.

Drenttel links to a 2004 New Yorker article by Malcolm Gladwell called Something Borrowed. It's worth revisiting in today's climate of Kaavya Viswanathan.

Gladwell begins by telling about a play that borrowed way too liberally from a real person's life, and then from a profile Gladwell wrote on the person. But further on in the article, he visits a friend who "works in the music industry" who plays him endless songs that resemble other songs in scandalous ways:

- The bass line in Shaggy's "Angel" and Steve Miller's "The Joker"

- Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love" and Muddy Waters's "You Need Love"

- Shabba Ranks's "Twice My Age" and Terry Jacks's "Seasons in the Sun"

- Wham!'s "Last Christmas" and Barry Manilow's "Can't Smile Without You" AND Kool and the Gang's "Joanna"

- Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and Boston's "More Than a Feeling"

This friend could apparently go on like that all night. And that's what music is about for him -- endless riffs on previous riffs. Gladwell writes:

"... if Kurt Cobain couldn't listen to 'More Than a Feeling' and pick out and transform the part he really liked we wouldn't have 'Smells Like Teen Spirit'—and, in the evolution of rock, 'Smells Like Teen Spirit' was a real step forward from 'More Than a Feeling' ... A successful music executive has to understand the distinction between borrowing that is transformative and borrowing that is merely derivative."

Couldn't that go for all art?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home