When it comes to art, are regular Americans unsophisticated, anti-intellectual clods, or are they (we?) just steadfast and uncompromising in their taste?

I'm a reasonably well educated and fairly progressive, but my reaction to contemporary art isn't always quiet. The last Whitney Biennial (which

I wrote about in April) embarrassed me and irritated me with all its self-indulgent faux outsider art. Why the visceral reaction?

The latest issue of

The Nation may provide a clue. Art critic Peter Plagens, in a review of Michael Kammen's new book

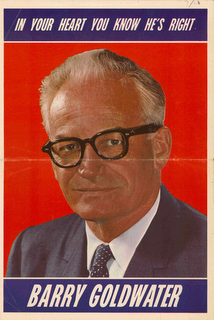

Visual Shock: A History of Art Controversies in American Culture, begins with a quote from President Harry Truman. When the president saw some paintings the State Department bought for a traveling exhibit of American art in 1947, he said, "If that's art, I'm a Hottentot."

Plagens explains the cultural climate:

What did Americans want? In the 1930s, the influential Chicago organization Sanity in Art provided a wonderfully summary answer when it took a position in favor of "rationally beautiful" art. Although the group failed to specify the exact ingredients, what a Midwestern art professor once told me after a lecture I gave at his college seems about right: Americans want, first, signs of a special talent. Second is lots of evident labor; third comes nonabject materials. The fourth requisite is realism, followed by noble (or at least not ignoble) content. Nowadays, you might add to the list political correctness of one sort or another. (In 1999 a photo blowup of Robert E. Lee in a Confederate uniform was ordered removed from the roster of famous Americans on the Canal Walk in Richmond, Virginia, until it could be replaced by one of the general in civvies.) And hanging over everything is the presumption of the constitutional right of every American never, ever to be offended by anything. Ours is a cultural, as much as a political, democracy, where plebeian opinions about art ought to count--we think--just as much as those of any effete egghead aficionado with a whole bunch of degree initials after his name. We bristle at authority in matters of aesthetics, and we're willing to go to the mat about it. We, too, are wont to proclaim, "If that's art, then I'm a Hottentot."

The emphasis above is mine, but let's look at that list again.

Americans think that art ought to show:

1. Obvious skill in craft.

2. Obvious signs of labor.

3. Use of high-quality materials.

4. Realistic depictions of real things.

5. Depiction of noble subjects, or subjects that are not ignoble.

And, later:

6. Sensitivity ot cultural mores.

Now look at a summary of what I said was wrong with the Whitney Biennial:

1. The art looks like it took absolutely no effort.

2. Some art really was pieces of garbage. Would I get in trouble for littering here?

3. Some of this art looks like the result of a bad idea and some talent or a good idea and no talent.

4. Some of the longer wall placards explaining the adjacent art are so opaque, they could be referring to any art there.

5. The art is self-indulgent.

6. Lots of art here looks like kindergarten craft projects.

7. Few of the artists here show any signs of acknowledging, much less assimilating the art of their predecessors.

So, in my opinions about art, I really sound like a cranky American from the 30s. On the other hand, I'm not so orthodox in my view of art that I think art should always have meaning. My favorite art confounds me. It's stuff that defies understanding in a way that encourages me to keep looking at it.

In the latest issue of the modern design magazine

Dwell, there's a capsule review of an exhibit at Columbus, Ohio's

Wexner Center for the Arts. The idea of the exhibit sounds great: Photographer Louise Lawler takes pictures of art in the places collectors, gallerists, and other have put it -- in homes, museums, galleries, auction houses, etc. The exhibit explores how a piece's setting affects the way we see it. Great idea.

But

Dwell's blurb on the exhibit troubles me:

"It's trite, but true: Many people still buy artwork to match their decor. Though it's easy to hang a painting that complements your chaise longue, most people are oblivious to the impact this has on the art itself."

I would venture that most people are oblivious to their surroundings in general. Over-stimulation does that. But I take issue with the idea that choosing art for the way it will look in your space is a lesser judgment than choosing a piece of art for its meaning.

An average American isn't going to hang a Nazi banner in his or her living room because the colors match the couch and the pretty pinwheel shape echoes the pattern on the Persian rug. Of course not. Any sane person will take any obvious meaning into account before choosing something for its looks.

It reminds me of an anecdote I once heard about the actor Sylvester Stallone. He allegedly decked out a room in fake books to give it a library feel. He either re-bound hundreds of random hardcovers in leather, or commissioned a facade of bookbindings, all for looks. Which is worse: a guy who has a library full of books he hasn't read or a guy who has a fake library? Assuming Stallone didn't just buy old books by the foot, I'd say the guy who doesn't leave himself room to redeem himself is worse. If Stallone can't stumble into his library one night and accidentally learn something, he's a real clod.

My point is that looks count. They aren't everything, but they have a meaning equal to the cultural and intellectual and historical meaning in art. Choosing a piece of art because it looks good in your pad isn't trite unless you are totally unaware of its other qualities.

The Whitney Biennial gave us too much meaning, often opaque, private meaning, and not enough beauty to keep us around to search for the meaning. In short, the pieces I disliked (and I should repeat that I didn't dislike

everything) were pieces that didn't show any of the first five qualifications from above. If it doesn't show skill in craft, it could at least show that someone worked hard on it. If it doesn't use high-quality materials, at least it could use junk to depict something real. You get the point.

This is why I loved the

American Folk Art Museum here in New York. They have a three feet-tall tower of chicken bones painted gold, made by a guy in Detroit who ate a lot of fast food chicken. They have a series of baseball cards that a guy embroidered out of the colored threads from his tube socks. The detail is exquisite. They have an area rug from the thirties woven out of Wonder Bread bags. It's very colorful. Here are strange and beautiful things created out of mundane materials.

What do

you think art should be? Comment. Let me know what you think.

Labels: art